See my post

— Roger W. Smith

Ben and Jerry’s – WSJ 3-19-2024

Posted here:

Ben & Jerry’s Owner Loses Its Taste for Ice Cream

Unilever plans to spin off its ice-cream business, which includes Magnum and Popsicle, and could consider a sale

By Saabira Chaudhuri

The Wall Street Journal

March 19, 2024

My business journalism instructor, Gilbert T. Sewall, was correct when he observed that the Wall Street Journal is notable for the excellence of its writing per se.

The best term I can come up with to describe this piece is limpid.

Everything is covered, succinctly. The facts have all been reported, are all there.

The business issues are made clear.

A layman (i.e., someone not in the business world) can enjoy this piece. Pithy phrases achieve this result:

Ben & Jerry’s owner Unilever has lost its taste for the business.

Ben & Jerry’s, once regarded by analysts as a jewel in Unilever’s crown, has turned into something of a thorn in its side.

Ben & Jerry’s hasn’t shied away from taking a stand on social causes.

Ice cream has been a tough business for … consumer-goods companies. …

Our high school English teacher taught us about topic sentences. Here we see embedded “topic sentences” that ensure that the reader does not get lost and gets the import of the piece.

— posted by Roger W. Smith

March 2024

Exemplified by … MYSELF.

What I would say (advise) is: cover the content of the book, what it’s about, what should be noted.

And: give your reviewer’s opinion of the book and whether it (implicitly) is worth reading.

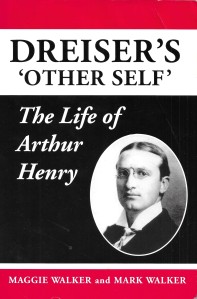

Roger W. Smith review of Arthur Henry bio – Dreiser Studies, winter 2005

— posted by Roger W. Smith

‘Rare Six-Planet System Discovred in Milky Way’ – WSJ 11-29-2023

Posted here is the following article (text plus marvelous photos):

Rare Six-Planet Star System Discovered in Milky Way: Worlds orbiting a sun-like star 100 light-years from Earth could unlock secrets surrounding the formation of our solar system

By Aylin Woodward

The Wall Street Journal

November 29, 2023

I have been studying writing all my life. I know a good writer (and good writing) when I see one.

Both the famous ones and writers whom I encounter in my daily reading.

Aylin Woodward is a science writer for The Wall Street Journal. Her work is superb.

“A family of six gaseous worlds circling like rhythmic dervishes around a sun-like star will soon help astronomers better understand how planetary systems like our own formed and evolved.

“This newly discovered system, about 100 light-years from Earth, is unusual because its planets orbit a bright host star in a pattern that appears unchanged since its birth at least 4 billion years ago, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.”

This is a very effective lead. Note how in the first paragraph, in just once sentence, the whole article is “capsulized.” The scope and importance of the subject, the findings, are stated with admirable concision.

The rest of the piece speaks for itself. My high school English teacher would have given it an A+.

I know from experience how difficult it is to adhere to word limits and write a brief article which reads well and sustains reader interest, while getting all the facts in (no easy task) and making their significance clear. Often the latter involves quotes — in this case from experts whom the author, Ms. Woodward, interviewed. All the facts and quotes have to be blended in skillfully without interrupting the flow of the piece.

While never losing sight of the overall significance of the findings and their import, This is done by the writer adhering to principles of writing such as unity and coherence

All of the best writers — including novelists — do this: mix the general with the specific. facts (narration) with exposition.

— posted by Roger W. Smith

November 30, 2023

Emerson, ‘Montaigne; Or, The Skeptic’

I was eager to read Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Montaigne; Or, The Skeptic,” which was published in his Representative Men: Seven Lectures (1850). I was disappointed and had a similar experience in reading Emerson that I have discussed in an earlier post:

Non-Sequaciousness (Emerson; also Carlyle)

Among the objectives of my posts on this site is to discuss “bad writing” and why even purportedly good writers fail.

I am very interested in Montaigne. I wanted to know what Emerson had to say about him. On about the seventh or eighth page of the essay, I found what I was looking for.

I found it tough to wade through the long introduction, and I had to dig and “extract” the stuff that I was interested in and the ((to me) salient points from a mass of glowing verbiage.

In his essay on non-sequaciousness (published in 1900) , Patrick Dillon states

… Emerson is, of all modern writers, the least fitted to be relied on as a literary model. The sparks he emits and the shocks he causes are dazzling and exciting; and his ideas are brilliant as the cascade’s spray; but it will be admitted that the effect of such a writer, taken as a model £or literary novices, must be in the last degree disastrous. The youthful mind is vastly inclined to vagueness, and, like Milton’s spirits, “finds no end, in wandering mazes lost.” Whatever, then, tends to encourage this tendency, must be fatal to that ratiocination, which, says Cardinal Newman, “is the great principle of order in thinking, reducing chaos to harmony.

Try reading the first few pages or paragraphs of Emerson’s essay for yourself.

— posted by Roger W. Smith

November 2023

new vocabulary words – August 2023

I have been told that I have an excellent vocabulary. Yet I keep learning new words from my reading.

See Word document above.

— Roger W. Smith

August 2023

Life did change for Tom and Maggie; and yet they were not wrong in believing that the thoughts and loves of these first years would always make part of their lives. We could never have loved the earth so well if we had had no childhood in it,—if it were not the earth where the same flowers come up again every spring that we used to gather with our tiny fingers as we sat lisping to ourselves on the grass; the same hips and haws on the autumn’s hedgerows; the same redbreasts that we used to call “God’s birds,” because they did no harm to the precious crops. What novelty is worth that sweet monotony where everything is known, and loved because it is known?

The wood I walk in on this mild May day, with the young yellow-brown foliage of the oaks between me and the blue sky, the white star-flowers and the blue-eyed speedwell and the ground ivy at my feet, what grove of tropic palms, what strange ferns or splendid broad-petalled blossoms, could ever thrill such deep and delicate fibres within me as this home scene? These familiar flowers, these well-remembered bird-notes, this sky, with its fitful brightness, these furrowed and grassy fields, each with a sort of personality given to it by the capricious hedgerows,—such things as these are the mother-tongue of our imagination, the language that is laden with all the subtle, inextricable associations the fleeting hours of our childhood left behind them. Our delight in the sunshine on the deep-bladed grass to-day might be no more than the faint perception of wearied souls, if it were not for the sunshine and the grass in the far-off years which still live in us, and transform our perception into love.

— George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss

MARVELOUS

— posted by Roger W. Smith

June 2023

My wife called something to my attention in the New York Times this morning. She had a problem with the second paragraph in the following story:

“On Eve of Trial, Discovery of Carlson Texts Set Off Crisis Atop Fox”

By Jim Rutenberg, Jeremy W. Peters, and Michael S. Schmidt

The New York Times

April 26, 2023

The second paragraph read:

Private messages sent by Mr. Carlson that had been redacted in legal filings showed him making highly offensive and crude remarks that went beyond the inflammatory, often racist comments of his prime-time show and anything disclosed in the lead-up to the trial.

I think I know why the sentence ended up the way it did. Because of newspaper-writing conventions regarding conciseness. The rule or standard is: Get rid of as many words as you can whenever and wherever they can be omitted (without omitting key facts or becoming unintelligible).

But there is a problem here.

comments OF HIS PRIME-TIME SHOW is vague and fuzzy. Were they comments that Carlson alone made (this is implied, but it could also include comments made by guests/interviewees)? Were they comments that he spoke or that were posted on the screen in bullet point fashion? In my mind it’s too vague. And awkwardly worded. It seems that comments ON his prime-time show would be better (sounds better to the ear). But then that’s not clear, because it could be anyone’s comments.

The best way to say it (undoubtedly) is comments made by Carlson on his prime-time show. This adds three words (the phrase made by Carlson on replaces the word of).

*****************************************************

My post

regarding Professor Strunk’s admonition, “Omit Needless Words.” (or, are long, complex sentences bad?)

is pertinent here.

I quoted Professor Brooks Landon in his lecture ““Grammar and Rhetoric” (lecture 2, “Building Great Sentences: Exploring the Writer’s Craft”; The Great Courses/The Teaching Company).

Unless the situation demands otherwise, sentences that convey more information are more effective than those that convey less. Sentences that anticipate and answer more questions that a reader might have are better than those that answer fewer questions. Sentences that bring ideas and images into clearer focus by adding more useful details and explanation are generally more effective than those that are less clearly focused and that offer fewer details.

Many of us have been exposed over the years to the idea that effective writing is simple and direct, a term generally associated with Strunk and White’s legendary guidebook The Elements of Style, or we remember some of the slogans from that book, such as, “Omit needless words.” … [Stunk concluded] with this all important qualifier: “This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that he make every word tell.” … Strunk’s concern is specifically with words and phrases that do not add propositions to the sentence [e.g., “owing to the fact that” instead of “since”].” … “Omit needless words” is great advice, but not when it gets reduced to the belief that shorter is always better, or that “needless” means any word without which the sentence can still make sense.

*****************************************************

Addendum:

My journalism school instructor, New York Times city reporter Maurice (Mickey) Carroll, taught me to tighten up my stories. His editing was invaluable. Here is an example from one of my assignments.

So I understand and appreciate the need for conciseness in newspaper reporting. But I also think Professor Landon’s astute observations should be kept in mind.

— posted by Roger W. Smith

April 27, 2023

Whitman to Anson Ryder, Jr. August

Posted here (PDF above) are two letters from Walt Whitman letter to Anson Ryder, Jr., dated August 15 and 16, 1865.

*****************************************************

A good letter mixes the general with the specific.

Emotion — feeling for the person addressed — with material that is of topical and anecdotal interest to both the letter writer and the recipient, creating a conversational-type bond.

— posted by Roger W. Smith

March 2023

*****************************************************

See also my post:

A Walt Whitman Letter; and, What Can Be Inferred from It about Letter Writing in General

A Walt Whitman Letter; and, What Can Be Inferred from It about Letter Writing in General